Reporting Highlights

- Vacuum: As President Donald Trump guts the principle federal workplace devoted to stopping terrorism, states say they’re left to take the lead in spotlighting threats.

- Gaps: Some state efforts are sturdy, others are fledgling and but different states are nonetheless formalizing methods for addressing extremism.

- Vulnerabilities: With the federal authorities largely retreating from specializing in extremist risks, prevention advocates say the specter of violent extremism is more likely to improve.

These highlights have been written by the reporters and editors who labored on this story.

Below the watchful gaze of safety guards, dozens of individuals streamed by means of metallic detectors to enter Temple Israel one night this month for a city corridor assembly on hate crimes and home terrorism.

The cavernous synagogue exterior of Detroit, certainly one of a number of homes of worship alongside a suburban strip nicknamed “God Row,” was on excessive alert. Police automobiles shaped a zigzag within the driveway. Solely registered friends have been admitted; no purses or backpacks have been allowed. Attendees had been knowledgeable of the placement simply 48 hours prematurely.

The extraordinary safety delivered to life the risk image described onstage by Michigan Legal professional Normal Dana Nessel, the recipient of vicious backlash as a homosexual Jewish Democrat who has led high-profile prosecutions of far-right militants, together with the kidnapping plot concentrating on the governor. Nessel spoke as a slideshow detailed her workplace’s hate crimes unit, the primary of its variety within the nation. She paused at a bullet level about working “with federal and native legislation enforcement companions.”

“The federal half, not a lot anymore, sadly,” she mentioned, including that the wording ought to now point out solely state and county companions, with assist from Washington “TBD.”

“The federal authorities used to prioritize home terrorism, and now it’s like home terrorism simply went away in a single day,” Nessel advised the viewers. “I don’t assume that we’re going to get a lot in the way in which of cooperation anymore.”

Credit score:

Brittany Greeson for ProPublica

Throughout the nation, different state-level safety officers and violence prevention advocates have reached the identical conclusion. In interviews with ProPublica, they described the federal authorities as retreating from the combat towards extremist violence, which for years the FBI has deemed the most lethal and active domestic concern. States say they’re now largely on their very own to confront the type of hate-fueled threats that had turned Temple Israel right into a fortress.

The White Home is redirecting counterterrorism personnel and funds towards President Donald Trump’s sweeping deportation marketing campaign, saying the southern border is the best home safety risk dealing with the nation. Millions in budget cuts have gutted terrorism-related legislation enforcement coaching and shut down studies monitoring the frequency of assaults. Trump and his deputies have signaled that the Justice Division’s give attention to violent extremism is over, beginning with the president’s clemency order for militants charged within the storming of the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

On the bottom, safety officers and extremism researchers say, federal coordination for stopping terrorism and focused violence is gone, resulting in a state-level scramble to protect efforts now not supported by Washington, together with hate-crime reporting hotlines and assist with figuring out threatening conduct to thwart violence.

This 12 months, ProPublica has detailed how federal anti-extremism funding has helped native communities avert tragedy. In Texas, a rabbi credited coaching for his actions ending a hostage-taking standoff. In Massachusetts, specialists work with hospitals to establish younger sufferers exhibiting disturbing conduct. In California, coaching helped thwart a possible faculty taking pictures.

Absent federal path, the combat towards violent extremism falls to a hodgepodge of state efforts, a few of them sturdy and others fledgling. The result’s a patchwork method that counterterrorism specialists say leaves many areas uncovered. Even in blue states the place extra political will exists, funding and applications are more and more scarce.

“We at the moment are going to ask each local people to attempt to get up its personal effort with none kind of steerage,” mentioned Sharon Gilmartin, govt director of Protected States Alliance, an anti-violence advocacy group that works with state well being departments.

Federal companies have pushed again on the concept of a retreat from violent extremism, noting swift responses in current home terrorism investigations akin to an arson assault on Democratic Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro in April and a automotive bombing this month exterior a fertility clinic in California. FBI officers say they’re additionally investigating an assault that killed two Israeli Embassy staff members exterior a Jewish museum in Washington in a probable “act of focused violence.”

Federal officers say coaching and intelligence-sharing programs are in place to assist state and native legislation enforcement “to establish and reply to hate-motivated threats, akin to these concentrating on minority communities.”

The Justice Division “is targeted on prosecuting criminals, getting unlawful medicine off the streets, and defending all People from violent crime,” mentioned a spokesperson. “Discretionary funds that aren’t aligned with the administration’s priorities are topic to evaluate and reallocation.” The DOJ is open to appeals, the spokesperson mentioned, and to restoring funding “as applicable.”

In an e mail response to questions on particular cuts to counterterrorism work, White Home spokesperson Abigail Jackson mentioned Trump is maintaining guarantees to safeguard the nation, “whether or not it’s maximizing using Federal assets to enhance coaching or establishing process forces to advance Federal and native coordination.”

Michigan, lengthy a hotbed of anti-government militia exercise, was an early adopter of methods to combat home extremism, making it a goal of conservative pundits who accuse the state of criminalizing right-wing organizing. An anti-Muslim group is difficult the constitutionality of Nessel’s hate crimes unit in a federal suit that has dragged on for years.

In late December, after a protracted political battle, Michigan adopted a new hate crime statute that expands an outdated legislation with additions akin to protections for LGBTQ+ communities and folks with disabilities. Proper-wing figures lobbed threatening slurs on the writer, state Rep. Noah Arbit, a homosexual Jewish Democrat who spoke alongside Nessel at Temple Israel, which is in his district and the place he celebrated his bar mitzvah.

Arbit acknowledged that his story of a hard-fought legislative triumph is dampened by the Trump administration’s backsliding. On this political local weather, Arbit advised the viewers, “it’s arduous to not really feel like we’re getting additional and additional away” from progress towards hate-fueled violence.

The politicians have been joined onstage by Cynthia Miller-Idriss, who leads the Polarization & Extremism Research & Innovation Lab at American College and is working with a number of states to replace their methods. She referred to as Michigan a mannequin.

“The federal authorities is gone on this concern,” Miller-Idriss advised the gang. “The longer term proper now’s within the states.”

Credit score:

Brittany Greeson for ProPublica

“The Solely Diner in City”

Some 2,000 miles away in Washington state, this month’s assembly of the Home Extremism and Mass Violence Activity Power featured a particular visitor: Invoice Braniff, a current casualty of the Trump administration’s about-face on counterterrorism.

Braniff spent the final two years main the federal authorities’s primary workplace devoted to stopping “terrorism and focused violence,” a time period encompassing hate-fueled assaults, faculty shootings and political violence. Housed within the Division of Homeland Safety, the Middle for Prevention Packages and Partnerships handled these acts as a urgent public well being concern.

A part of Braniff’s job was overseeing a community of regional coordinators who helped state and native advocates join with federal assets. Advocates credit score federal efforts with averting assaults by means of funds that supported, for instance, coaching that led a pupil to report a gun in a classmate’s backpack or applications that assist households intervene earlier than radicalization turns to violence.

One other mission helped states develop their very own prevention methods tailor-made to native sensibilities; some give attention to training and coaching, others on beefing up enforcement and intelligence sharing. By early this 12 months, eight states had adopted methods, eight others have been within the drafting stage and 26 extra had expressed curiosity.

Speaking via teleconference to the Seattle-based process pressure, Braniff mentioned the workplace is now “being dismantled.” He resigned in March, when the Trump administration slashed 20% of his workers, froze a lot of the work and signaled deeper cuts have been coming.

“The method that we adopted and evangelized over the past two years has confirmed to be actually efficient at reducing hurt and violence,” Braniff advised the duty pressure. “I’m personally dedicated to maintaining it entering into Washington state and in the remainder of the nation.”

A Homeland Safety spokesperson didn’t handle questions in regards to the cuts however mentioned in an e mail that “any suggestion that DHS is stepping away from addressing hate crimes or home terrorism is just false.”

Since leaving authorities, Braniff has joined Miller-Idriss on the extremism analysis lab, the place they and others aspire to construct a nationwide community that preserves an effort as soon as led by federal coordinators. The freezing of prevention efforts, financial uncertainty and polarizing rhetoric within the run-up to the midterm elections create “a strain cooker,” Braniff mentioned.

Related discussions are occurring in additional than a dozen states, together with Maryland, Illinois, California, New York, Minnesota and Colorado, in accordance with interviews with organizers and recordings of the conferences. In a single day, grassroots efforts that after complemented federal work have taken on outsized urgency.

“If you’re the one diner on the town, the meals is way more wanted,” mentioned Brian Levin, a veteran extremism scholar who leads California’s Fee on the State of Hate.

Levin, talking in a private capability and never for the state panel, mentioned commissioners are “pedaling as quick as we will” to fill the gaps. Levin has tracked hate crimes since 1986 and this month launched up to date analysis exhibiting incidents nationally hovering close to document highs, with sharp will increase final 12 months in anti-Jewish and anti-Muslim concentrating on.

The fee additionally unveiled outcomes of a examine performed collectively with the state Civil Rights Division and UCLA researchers exhibiting that greater than half one million Californians — about 1.6% of the inhabitants — mentioned that they had skilled hate that was probably felony in nature, akin to assault or property injury, within the final 12 months.

Prevention staff say that’s the type of information they will now not depend on the federal authorities to trace.

“For a fee like ours, it makes our specific mission now not a luxurious,” Levin mentioned.

Hurdles Loom

Some state-level advocates marvel how successfully they will push again on hate when Trump and his allies have normalized dehumanizing language about marginalized teams. Trump and senior figures have invoked a conspiracy principle imagining the engineered “alternative” of white People, because the president refers to immigrants as “poisoning the blood” of the nation.

Trump makes use of the “terrorist” label primarily for his political targets, lumping collectively leftist activists, drug cartels and pupil protesters. In March, he suggested that current assaults on Tesla automobiles by “terrorists” have been extra dangerous than the storming of the Capitol.

“The actions of this administration foment hate,” Maryland Legal professional Normal Anthony Brown, a Democrat, advised a meeting last month of the state’s Fee on Hate Crime Response and Prevention. “I can’t say that it’s solely chargeable for hate exercise, nevertheless it definitely appears to carry the lid and virtually encourages this exercise.”

A White Home spokesperson rejected claims that the Trump administration fuels hate, saying the allegations come from “hoaxes perpetrated by left-wing organizations.”

One other hurdle is getting buy-in from pink states, the place many politicians have espoused the view that hate crimes and home terrorism considerations are exaggerated by liberals to police conservative thought. The starkest instance is the embrace of a revisionist telling of the Capitol riots that performs down the violence that Biden-era Justice Division officers labeled as home terrorism.

The subsequent 12 months, citing First Modification considerations, Republicans opposed a home terrorism-focused invoice launched after a mass taking pictures concentrating on Black folks in Buffalo, N.Y.

The chief of 1 massive prevention-focused nonprofit that has labored with Democratic and Republican administrations, talking on situation of anonymity due to political sensitivities, mentioned it’s vital to not write off pink states. Some Republican governors have adopted methods after devastating assaults of their states.

A white supremacist’s rampage by means of a Walmart in El Paso in 2019 — the deadliest assault concentrating on Latinos in trendy U.S. historical past — prompted Texas Gov. Greg Abbott to create a domestic terrorism task force. And in 2020, responding to a string of high-profile assaults together with the Parkland highschool mass taking pictures, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis launched a focused violence prevention technique.

The pitch is vital, the nonprofit director mentioned. Republican officers usually tend to be swayed by efforts targeted on “violence prevention” than on combating extremist ideologies. “Use the language and the framing that works within the context you’re working in,” the advocate mentioned.

Nonetheless, gaps will stay in areas akin to hate crime reporting, companies for victims of violence and coaching to assist the FBI sustain with the newest threats, mentioned Miller-Idriss, the American College scholar.

“What feels terrible about it’s that there’s simply total states and communities who’re fully omitted and the place individuals are going to finish up being extra weak,” she mentioned.

Cautionary Story From Michigan

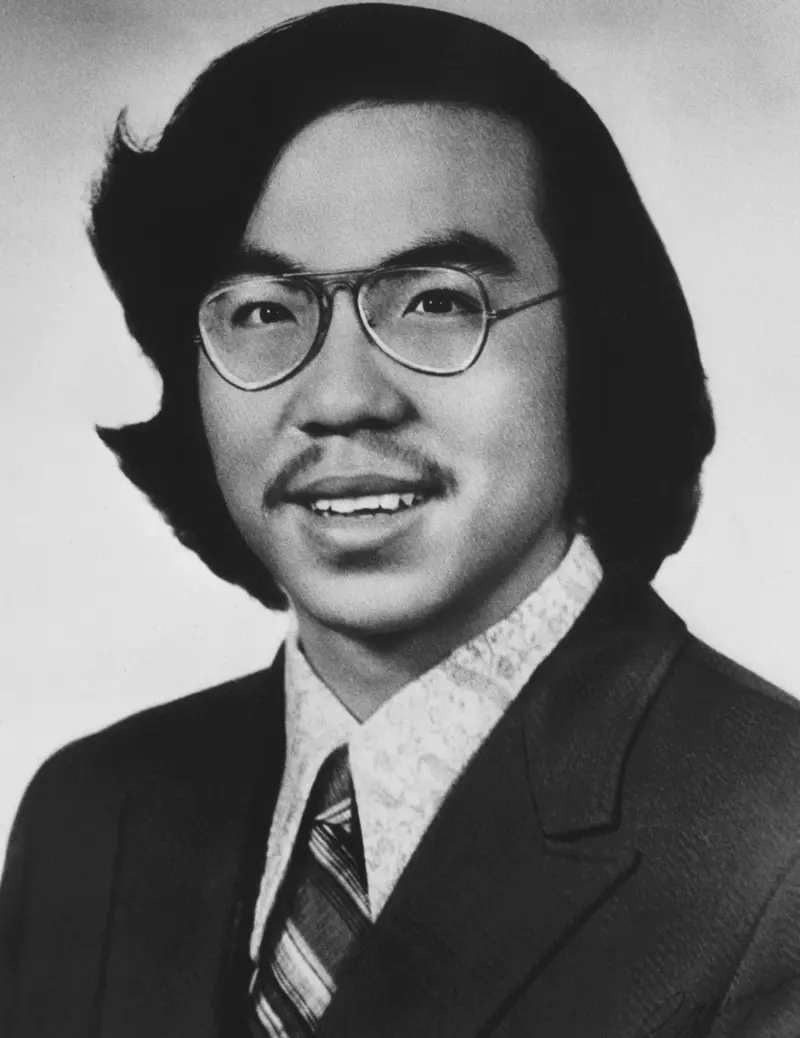

On a summer time night time in 1982, Vincent Chin was having fun with his bachelor celebration when two white auto staff at a nightclub exterior of Detroit focused him for what was then referred to as “Japan bashing,” hate speech stemming from anger over Japanese automotive corporations edging out American rivals.

The lads, apparently assuming the Chinese language-born Chin was Japanese, taunted him with racist slurs in a confrontation that spiraled right into a vicious assault exterior the membership. The lads beat 27-year-old Chin with a baseball bat, cracking his cranium. He died of his accidents 4 days later and was buried the day after his scheduled marriage ceremony date.

Credit score:

Bettmann/Getty Pictures

Asian People’ outrage over a choose’s leniency within the case — the assailants obtained $3,000 fines and no jail time — sparked a surge of activism in search of harder hate crime legal guidelines nationwide.

In Michigan, Chin’s killing impressed the 1988 Ethnic Intimidation Act, which was sponsored by a Jewish state lawmaker, David Honigman from West Bloomfield Township. Greater than three many years later, Arbit — the Jewish lawmaker representing the identical district — led the marketing campaign to replace the statute with laws he launched in 2023 and at last noticed adopted in December.

“It felt like kismet,” Arbit advised ProPublica in an interview just a few days after the occasion at Temple Israel. “That is the legacy of my neighborhood.”

However there’s a notable distinction. Honigman was a Republican. Arbit is a Democrat.

“It’s form of telling,” Arbit mentioned, “that in 1988 this was a Republican-sponsored invoice after which in 2023 it solely handed with three Republican votes.”

Some Republicans argued that the invoice infringes on the First Modification with “content-based speech regulation.” One conservative state lawmaker told a right-wing cable show that the aim is “to advance the unconventional transgender agenda.”

Arbit mentioned it took “sheer brute pressure” to enact new hate crimes legal guidelines on this hyperpartisan period. He mentioned state officers coming into the fray ought to be ready for social media assaults, doxing and dying threats.

In the summertime of 2023, Arbit was waylaid by a right-wing marketing campaign that lowered his detailed proposal to “the pronoun invoice” by spreading the debunked concept it will criminalize misgendering somebody. Local outlets fact-checked the false claims and Arbit made some 50 press appearances correcting the portrayal — however they have been drowned out, he mentioned, by a “disinformation storm” that unfold shortly by way of right-wing shops akin to Breitbart and Fox Information. The invoice languished for greater than a 12 months earlier than he may revive it.

In December 2024, the laws handed the Michigan Home 57-52, with a single Republican vote. In contrast, Arbit mentioned, the invoice was endorsed by an affiliation representing all 83 county prosecutors, nearly all of them Republicans. Those that see the results up shut, he mentioned, are much less more likely to view violent extremism by means of a partisan lens.

“These are actual safety threats,” Arbit mentioned. “Shouldn’t we would like a society wherein you’re not allowed to focus on a bunch of individuals for violence?”