All too typically, when mother and father can’t afford protected housing, the answer youngster welfare companies provide is placing their kids in foster care.

It was a Sunday this previous June, and Virginia Ortega was heading to work at her job cleansing resort rooms, placing in extra time so she might pay her lease. She requested her son Cesar (a pseudonym), an autistic 16-year-old who additionally suffers from hallucinations, if she ought to discover somebody to look at him whereas she labored, however he mentioned no, he was sufficiently old to remain dwelling alone. When Ortega returned to her squat, triangle-roofed one-story home in southeastern Kansas Metropolis, Missouri, after work, the entrance door was hanging open and Cesar was nowhere to be discovered. Frantic, she requested her neighbors what had occurred. One instructed her that the police had taken her son whereas she was at work.

Ortega, who’s initially from Mexico and speaks Mixtec and Spanish, mentioned a caseworker with Missouri’s youngster welfare company ultimately instructed her that her son was taken as a result of she doesn’t have air-con. In Missouri, landlords are required to offer warmth however not air-con, and her landlord has refused to get a unit for her. She doesn’t have the cash to purchase one herself. She instructed me that the caseworker instructed her, “No es seguro vivir conmigo”: that it’s not protected for her son to stay together with her.

Ortega had labored onerous to make her home as protected as she might. Sitting on the tile flooring of her small front room in September—her solely furnishings is a black love seat and a naked mattress on the ground of her bed room—she instructed me that when she moved into the home, it was lined with rat feces. She received it as clear as potential, however the place nonetheless wanted repairs: The kitchen cupboard doorways have been hanging off their hinges, and there was a big gap punched within the tile over her bathtub. Ortega tried to get her landlord to repair it up, however as a substitute the owner retaliated: She accused Ortega of utilizing an excessive amount of water and fuel after which shut the water off. Ortega want to transfer, however she will’t afford to place down a deposit on one other dwelling, and she or he doesn’t know the way to apply for a housing voucher or for public housing. She has no household right here in the USA to assist.

After we spoke, months after Cesar was taken, Ortega nonetheless knew nothing about the place he was or who was caring for him. “No sé nada,” she mentioned, silently crying: I don’t know something. She hadn’t been in a position to see him for 3 months, the longest they’d ever been aside. “Extraño mucho a mi hijo,” she mentioned, holding her fingers over her eyes: I miss my son very a lot. “Nomás puedo llorar”: All I can do is cry.

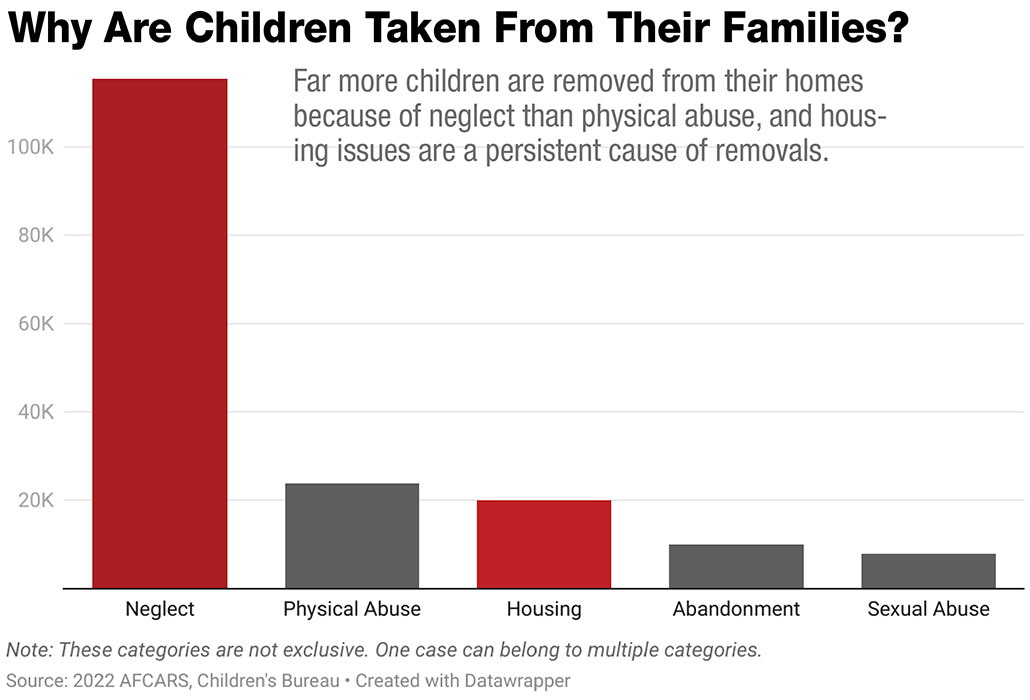

You would possibly assume that youngster welfare businesses take away kids from their households primarily over suspicions of bodily or sexual abuse. However the actuality is that removals for the extra nebulous class of “neglect”—which ranges from locking a toddler in a closet to leaving a toddler within the care of an older sibling so a mother or father can go to work—are way more frequent. In 2022, the newest 12 months for which federal knowledge is out there, neglect was the premise for 62 p.c of removals within the nation, which meant 115,473 kids have been taken from their households for that reason. In Missouri, neglect made up two-thirds of all referrals to a toddler welfare company in 2024.

Most neglect instances stem from monetary deprivation and its results—resembling insufficient meals, clothes, or shelter. Analysis means that it’s poverty that drives these issues, not the mother and father’ unwillingness to deal with them. “There’s a considerable physique of proof that once you scale back poverty, there may be much less child-welfare-system involvement and fewer neglect particularly,” mentioned William Schneider, an affiliate professor on the College of Illinois Urbana-Champaign with a give attention to youngster welfare.

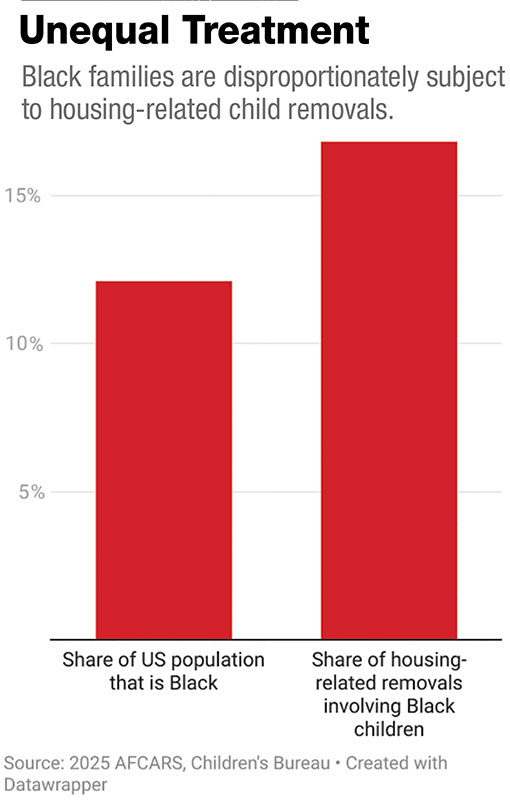

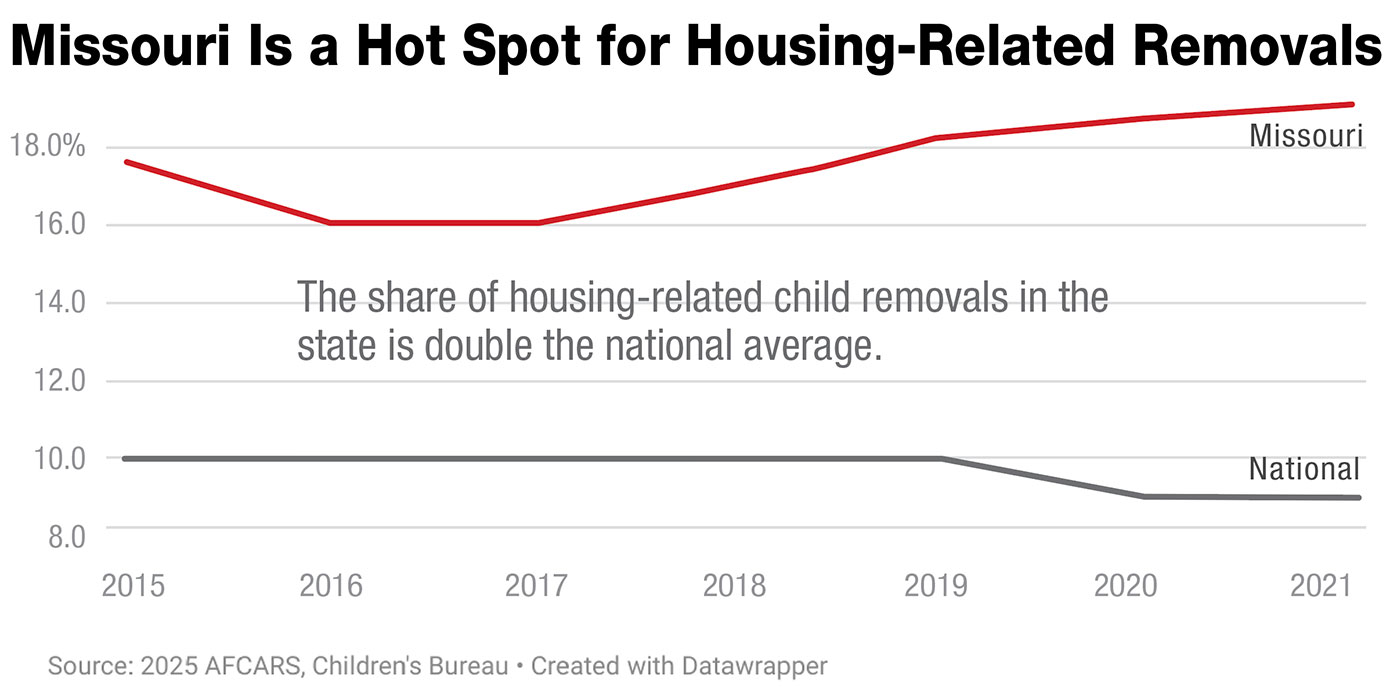

The shortcoming to afford respectable housing is a persistent driver of kid neglect instances. Yearly since 2015, insufficient or unsafe housing was cited as a motive for removing in about 10 p.c of all instances by which kids have been taken from their households by youngster welfare businesses, whilst the full variety of kids faraway from their households has declined, based on federal Adoption and Foster Care Evaluation and Reporting System knowledge. In 2023, the newest 12 months for which knowledge has been launched, practically 16,000 kids who have been faraway from their properties, representing 9 p.c of all removals, have been deemed to stay in substandard housing. These kids could have been eliminated for a mixture of things that might additionally embody a mother or father’s substance abuse or psychological sickness, however some kids are eliminated solely as a result of their households’ housing is insufficient. In 2021, the newest 12 months for which there’s knowledge, at the least 1,467 kids have been taken from their households due to housing points alone. This phenomenon disproportionately impacts Black households; on common between 2013 and 2021, practically 20 p.c of youngsters eliminated due to housing have been Black, despite the fact that Black folks make up about 12 p.c of the inhabitants.

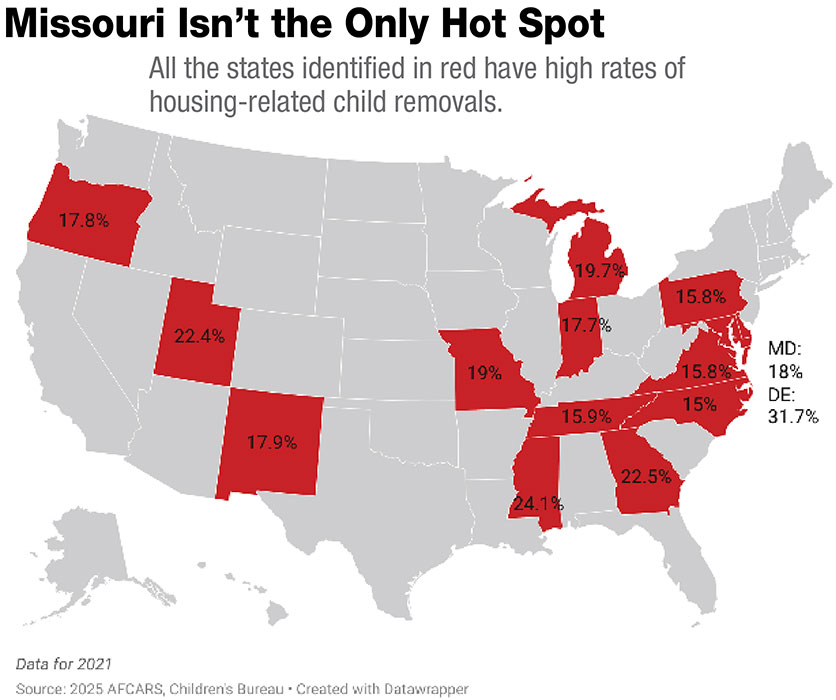

These numbers are most probably an undercount due to variations in how caseworkers in numerous jurisdictions fill out paperwork. Even so, some states are clearly scorching spots for housing-related removals. Missouri is one in all them, as are states as various as Georgia, Maine, Michigan, and New Mexico. In Missouri, between 2013 and 2021, a mean of 18 p.c of youngsters per 12 months who have been faraway from their households have been eliminated at the least partially due to their housing. In 2019, earlier than the variety of removals fell in the course of the pandemic, the state eliminated 138 kids from their households solely for that reason. Black kids in Missouri are additionally disproportionately affected: On common, they accounted for 14 p.c of removals in the identical interval, despite the fact that Black folks make up 11 p.c of the state’s inhabitants.

In Missouri, a substandard residence is motive sufficient for judges to conform to removals, mentioned Kathleen Dubois, a retired household courtroom lawyer in St. Louis. “No person blames the owner,” she instructed me. “They simply take away the youngsters.” Kathy Connors, the chief director of the St. Louis homeless shelter Gateway180, sees the identical factor: There are an “terrible lot” of cases by which moms dwelling in her shelter have their kids taken away if they’ll’t discover everlasting housing quick sufficient.

The stakes are extremely excessive. “Separating a mother or father and a toddler causes trauma nevertheless it comes about,” mentioned Josh Gupta-Kagan, a Columbia Regulation College professor who makes a speciality of youngster neglect and abuse legislation. One research in Sweden discovered that kids faraway from their households are more likely to be hospitalized for psychological sickness and to commit suicide. When kids are taken from their households, even when they’re positioned in a caring foster dwelling, “you rip them from their faculty, you rip them from their neighborhood, their pals, and also you erode kinship relationships,” mentioned Clark Peters, an affiliate professor on the College of Missouri with a give attention to youngster welfare.

In the meantime, any removing begins a comparatively quick clock: If mother and father fail to reunify with their kids earlier than 15 months elapse, youngster welfare businesses should transfer to terminate parental rights. That’s when households threat dropping their kids eternally.

The top of Missouri’s Youngsters’s Division, Sara Smith, insists that caseworkers in her company use an individualized method in figuring out when a removing is critical. “In and of itself, we wouldn’t take homelessness as a report,” Smith asserted. “We might be taking a look at if the kid’s primary wants are met, if the household does have some form of housing.” As well as, she mentioned, an abuse or neglect report is just not the one choice out there; caseworkers could make a “preventative service referral,” which factors households to neighborhood organizations—nonprofits, church buildings—that may have the ability to present sources. Households also can select to do a “non permanent different placement settlement,” or TAPA, a voluntary course of exterior the courtroom system that locations kids with different members of the family. However Smith acknowledges that the division doesn’t spend its personal funds on securing or fixing housing for households. “Youngsters’s Division in and of itself doesn’t present…a few of the issues which are wanted for housing conditions,” she mentioned. “We actually do depend on our neighborhood companions.”

Missouri operates a statewide hotline for preliminary reviews of kid abuse and neglect. When hotline workers obtain a report, they’re prompted to notice “situations or content material of the family that are unsafe or unsanitary,” in addition to whether or not the utilities are turned off and if there’s a “lack of shelter.” A report is referred to an area youngster welfare division within the state when “lack of warmth or shelter, or unsanitary family situations are hazardous and will result in harm or sickness of the kid(ren) if not resolved.”

As soon as a report is funneled to an area division, a caseworker completes threat and security assessments. A degree will get added to a household’s threat rating if “present housing is bodily unsafe,” whereas homelessness provides two factors. One of many components included within the security evaluation is whether or not “the bodily dwelling situations are hazardous and instantly threatening to the kid’s well being and/or security.” This might embody “conditions the place important structural risks exist in dwelling (e.g., leaking fuel from range or heating unit, lack of water or utilities, uncovered and accessible electrical wires),” in addition to issues like “repeated insect and rodent bites” and “ongoing presence of animal feces.” If a number of security threats are current, and an intervention plan or TAPA is deemed inadequate, then the evaluation states that kids have to be eliminated. (Smith famous that the danger evaluation, which is 20 years outdated, is at the moment being redeveloped.)

Whereas the danger and security assessments are guides, loads comes right down to a caseworker’s instincts. “Doing this work for some time, once you go into a house the place you can not repair,” Smith mentioned.

Darrell Missey grew to become the director of Missouri’s Youngsters’s Division in 2022. A former decide who heard youngster welfare instances, he took the job with the objective of decreasing removals. “I used to be attempting to get folks to present people the chance to provide you with solutions moreover separating the household,” Missey mentioned. Nonetheless, he typically felt pressured to take away kids as a result of he didn’t have any housing to supply their households. Missey left the place in late 2024. Smith, his alternative, reassigned the particular person Missey had employed to work on removing prevention to a unique function and fired his deputy director, he mentioned. There’s a “mentality” that “pervades the state” of eradicating a toddler as a substitute of discovering a strategy to repair or discover housing, he added: “Missouri’s management is just not keen on stopping kids from coming into foster care.”

A singular side of Missouri’s youngster welfare system makes removals much more seemingly. As soon as the Youngsters’s Division determines {that a} youngster ought to be eliminated, caseworkers hand the case over to a juvenile officer, who has the only purview of deciding whether or not to hunt removals or reunifications. The officers are employed, supervised, and fired by the very judges that they petition to take away kids, which means there’s “no separation of powers,” Missey mentioned. And whereas the federal authorities requires state businesses to make efforts to stop removals and reunify kids with their mother and father, juvenile officers aren’t topic to these guidelines.

Some states have legal guidelines that say, at the least on paper, that kids shouldn’t be faraway from their households as a result of their mother and father can’t afford respectable housing. About half of states exempt mother and father’ monetary incapacity to offer issues like shelter for his or her kids from the definition of kid maltreatment. No less than three states have statues saying homelessness doesn’t represent neglect.

Missouri doesn’t. Whereas it has exceptions in its maltreatment statutes for corporal punishment and refusing medical care on non secular grounds, it has none for poverty or homelessness. And whereas removals are presupposed to happen solely when a toddler is at imminent threat of hurt, caseworkers typically think about housing points indications of that threat.

That’s what occurred to Lauren, whom I met at household courtroom in Kansas Metropolis. Her son John (each pseudonyms to guard the household’s privateness whereas their case is pending), now 9 years outdated, was born with persistent kidney illness. By means of tears, Lauren recalled that, just a few years in the past, each her mom and John have been hospitalized on the identical time. Attempting to take care of each of them, Lauren misplaced her job as a knowledge entry clerk. When it got here time to resume the lease on her dwelling in Kansas Metropolis, she declined, believing she would quickly transfer in together with her mom. Then her mom died. Lauren and John have been evicted, and so they ultimately moved into an extended-keep resort.

The resort wasn’t excellent, nevertheless it labored for them: They lived in a collection with a fridge, a range prime, and a desk and chairs. “That was like our dwelling,” Lauren mentioned. She had meals within the fridge, and she or he positioned the brand new garments she had purchased for John on hangers. “We have been sleeping good each evening. He was consuming, taking baths.” John was transported from the resort to high school and again. The opposite long-term residents of the resort grew to become their neighborhood. Between John’s Social Safety incapacity funds and Lauren’s earnings driving for DoorDash, she might cowl her prices.

Nonetheless, John’s physician repeatedly instructed her that she wanted to maneuver to everlasting housing, however the hospital social staff didn’t provide a lot assist. They gave her a chunk of paper itemizing sources she might contact—all of which she had already tried.

And Lauren nonetheless couldn’t get a full-time job. John’s dialysis occurred three days every week, 4 and a half hours at a time; he had different medical appointments and hospitalizations, too. “I spend extra of my time at this hospital than I can do at a job,” Lauren mentioned. However she’d developed a plan: She had determined to maneuver in with an aged cousin who lives alone in a three-bedroom home in Oklahoma Metropolis and has a spare automobile. In Oklahoma, Lauren heard, she might get off the ready checklist for a Part 8 rental voucher in a matter of months and at last get her personal housing. She had packed up and was even authorised for Medicaid and meals stamps there. All she was ready for was the hospital to ship her son’s information over to a brand new dialysis heart close to her cousin. She deliberate to maneuver earlier than Labor Day.

As an alternative, a hospital worker known as the state hotline to report her to the Youngsters’s Division. The paperwork outlining the explanations for her son’s removing notes that they’d stayed within the resort for over a 12 months. That introduced an imminent threat, based on the division, as a result of John had been faraway from the kidney donor checklist when it was found that Lauren didn’t have everlasting housing, despite the fact that the anticipate a transplant usually lasts years. The hospital additionally claimed that John wasn’t taking his medicines and that he was lacking his appointments—a declare that Lauren vehemently denies. Even when she briefly didn’t have a automobile, they by no means missed appointments, she mentioned, exhibiting up late solely when the medical transport was late.

Lauren’s son is now dwelling together with her eldest daughter. Although he’s with a member of the family, the expertise has been traumatic. For the primary week, Lauren couldn’t see or speak to him. “They handled me like I used to be an abusive mom,” she mentioned. The 2 had by no means spent that lengthy aside. John cried day by day and started shedding weight. Ultimately, Lauren was permitted 10-minute telephone conversations with him. “He cried and cried—he cried when he received on the telephone with me, he cried after they made him get off,” she mentioned. Lauren herself couldn’t sleep or eat. “I used to be simply sitting up ready for the subsequent name.”

After we met in September, she was allowed to see him, however just for an hour whereas he was at dialysis, and solely when somebody on the Youngsters’s Division was out there to oversee the go to. John cried each time she left. “He’s actually not himself,” Lauren mentioned. “I can simply see in his face he’s not comfortable.” He’s requested her if this all means she’s not his mom anymore and insists he doesn’t need a new mother. “I’m all he received. I’m all he is aware of,” she mentioned.

Lauren has been instructed she has to have everlasting housing to be reunited with John, and she or he’s attempting, however “it’s onerous,” she mentioned. She’s nonetheless on the ready checklist for Part 8 and public housing. “I simply don’t see how they’ll get away with doing this to folks,” she mentioned tearfully, heavy luggage underneath her eyes. “I nonetheless take excellent care of him, and I really feel like that ought to be all that issues.”

As soon as they’ve misplaced custody of a kid, households may be held to a fair increased commonplace earlier than they’ll reunite. Any state-level protections towards removals as a result of poverty or homelessness disappear in terms of whether or not and when kids can go dwelling. Caseworkers and judges have way more discretion to inform mother and father what they need to accomplish earlier than they’ll get their children again.

Ortega is coping with these hurdles now. To get her son again, a decide instructed her, she needed to have respectable housing, a job, and $3,000 in a checking account, she instructed me. However after Cesar was eliminated, she was fired—somebody at work had unfold a rumor that she’s a nasty mom. Ortega suffers from leukemia, which makes it onerous for her to seek out one other job. The courtroom order eradicating Cesar mentioned she had been referred to affordable-housing applications, however Ortega couldn’t make use of that referral. She will be able to’t learn; her mom didn’t ship her to high school.

To make issues even worse, she now not will get the $960 a month that Cesar receives in Social Safety incapacity advantages. When she went to gather the checks, she was instructed that they’re going as a substitute to whoever is caring for Cesar. After we met, she was on the verge of dropping her housing with none earnings.

“No le hice nada a mi niño,” she mentioned: I by no means did something to harm my son. However that’s not sufficient within the courtroom’s eyes. “Si no tengo trabajo, no me pueden entregar a mi hijo,” she mentioned: If I don’t have work, they’ll’t deliver again my son. “Si no tengo casa mejor, no me lo van a entregar a mi”: If I don’t have a greater home, they’re not going to deliver him again to me.

Whether or not or not a toddler was initially eliminated due to issues with housing, youngster welfare businesses typically insist {that a} household safe or enhance their housing state of affairs earlier than reunification. In Missouri, the requirements are “actually robust” about what qualifies as an acceptable dwelling, Dubois mentioned, and so they exclude brothers and sisters sharing rooms or mother and father sharing bedrooms with their kids. Residing on the Gateway180 shelter is usually not thought of ample housing to permit mother and father to get their kids again, Connors mentioned. She has seen many households who come to the shelter working to reunify with their kids. However since she started working there in 2016, she has seen solely 4 profitable reunifications. “It does seem to be it’s a state of affairs the place the goalpost retains getting moved additional and additional,” she mentioned. Three research performed since 1996 have concluded that 30 p.c of youngsters nationally might have been reunited with their households instantly if the households had ample housing.

The affordable-housing disaster makes this an much more troublesome barrier to beat. Housing prices for each renters and homeowners rose quicker than inflation final 12 months, with practically half of renters spending greater than a 3rd of their earnings on lease. The median lease jumped 4.1 p.c. Homelessness reached the best stage ever recorded.

An extended historical past of housing discrimination in the USA could clarify, at the least partially, the disproportionate impression of housing-related removals on Black households, with Missouri being no exception. Each Kansas Metropolis and St. Louis, the state’s largest cities, developed redlining maps that banks used to disclaim loans in “undesirable” areas. Within the Twenties, Kansas Metropolis builders adopted racial exclusion insurance policies that prohibited gross sales or leases to Black folks. St. Louis had an ordinance prohibiting Black folks from shifting into homes on predominantly white blocks. This legacy continues to be seen immediately. The dividing line within the metropolis is Delmar Boulevard: The realm north of it is filled with vacant and run-down buildings; instantly south of it, brand-new housing and health club complexes spring up.

The cheaper housing north of Delmar is usually very outdated and in want of serious repairs. “The landlords are actually infamous,” Dubois mentioned. In addition they ceaselessly resort to evictions. Household courtroom lawyer Laurie Snell mentioned the identical factor of Kansas Metropolis. “There are a variety of slumlords,” she instructed me.

Typically all that households want to stay stably housed and stop a toddler’s removing is a few more money. However whereas the Youngsters’s Division doesn’t use its funds to assist these households with housing, the company does immediately fund the housing wants of foster households, as federal legislation requires. In Missouri, licensed foster-care households obtain between $509 and $712 a month for a kid, relying on the kid’s age, to cowl housing and different primary wants, plus a further $91 a month for youngsters 3 years and youthful to cowl issues like method and diapers. They obtain between $320 and $700 a 12 months for clothes, in addition to month-to-month funds of as a lot as $2,034 for youngsters with “elevated wants.”

That form of cash would have been a godsend for A.M. and her husband, E.M. (they requested anonymity out of worry that talking out would deliver them again to the eye of the Youngsters’s Division), who’ve 4 kids, three of whom have mental or psychological disabilities. A.M. and E.M. misplaced the custody of some or all of their kids a number of occasions over the previous three many years. The primary time their household grew to become entangled within the youngster welfare system was in 1990, when A.M.’s mom known as the state hotline to report them. After exhibiting up at their St. Louis residence, a caseworker supplied them cleansing provides with out eradicating their son (then their solely youngster). However 5 years later, after A.M. was “hotlined” once more, the caseworker who visited their dwelling deemed it too soiled, and their son was eliminated. “It was heart-wrenching,” A.M. recalled. She suffers from melancholy in addition to bodily disabilities, however no allowance was made for any of her situations. She and E.M. needed to get the home clear and be sure that the utilities have been saved on, plus attend parenting lessons, to get their son again. It wasn’t straightforward; E.M. saved having to take day without work work to fulfill the necessities, and he nervous that he’d lose his job.

The final time their household was separated, after her kids’s faculty district known as the hotline, it took A.M. and E.M. a 12 months and a half to get again their youngest son, who’s autistic. He receives Social Safety incapacity funds, however whereas he was out of their dwelling, A.M. and E.M. not solely didn’t obtain these checks however have been made to pay about $200 a month in youngster help to the state. A.M. was nonetheless struggling to get on incapacity advantages herself; E.M. was placing in 14-hour days at work. “We nearly misplaced our dwelling,” A.M. mentioned. As soon as they have been reunited with their son, they received most of his Social Safety a refund, nevertheless it all went to their landlord to atone for lease.

Reminiscences of the removals nonetheless deliver A.M. to tears. “It appeared prefer it occurred each 5 years,” she mentioned. “All of it was due to the home.” Each time the youngsters have been taken, the foster households obtained month-to-month checks to take care of them. If these funds had as a substitute gone to A.M. and E.M., it “would have meant loads,” A.M. mentioned. “With the ability to pay our payments, really get the stuff the youngsters wished.”

“Right here in Missouri, they search for any and each excuse to take the child away,” E.M. added. “I believe the state would have saved some huge cash by serving to the organic mother and father get by way of no matter points there was.”

Certainly, analysis has discovered that when households get assist with housing, their involvement with youngster welfare businesses decreases. Throughout the pandemic, eviction moratoriums considerably drove down reviews of kid neglect. An in-depth research by the US Division of Housing and City Growth discovered that households who obtained housing vouchers had kids eliminated far much less typically than those that didn’t. One other HUD demonstration undertaking discovered that households who got supportive housing ended up getting their kids again at twice the speed of households who weren’t.

However most youngster welfare businesses don’t provide such interventions. One huge motive is that the federal authorities reimburses states for cash they spend supporting foster mother and father by way of Title IV-E of the Social Safety Act, which is the primary supply of kid welfare funding. Nevertheless it received’t reimburse state spending to immediately help start households. Ruth White, the chief director of the Nationwide Middle for Housing & Little one Welfare, argues that businesses produce other versatile funding they may use this manner, together with different Social Safety Act cash, funds from the Non permanent Help for Needy Households program, and state and native cash. However businesses and the array of nonprofits that work with them “are firstly involved with funding the equipment,” the kid welfare system itself, White mentioned.

“We don’t have an entitlement to shelter,” she added. “We have now an entitlement to foster care.”

Caseworkers, in the meantime, don’t usually give attention to serving to households with housing. Smith, the Missouri Youngsters’s Division head, mentioned she’s attempting to domesticate a tradition of “not simply giving households a stack of papers” to level them towards exterior sources however giving them “a heat handoff.” However as Ortega’s and Lauren’s experiences present, caseworkers nonetheless often simply hand out papers. Nationally, caseworkers are “already overloaded—it’s an extremely irritating job,” Schneider, the kid welfare scholar, mentioned. The median caseworker handles 55 instances a 12 months. The turnover in Missouri’s Youngsters’s Division was 28 p.c in fiscal 12 months 2025. Even when all a household wants, as in Ortega’s case, is an air conditioner, caseworkers could not have the funds—and would possibly resist calling round to seek out a company that does.

Caseworkers may really feel that this sort of work isn’t of their job description. They “have been skilled to consider selling particular person accountability,” Schneider mentioned. Dubois, the retired household courtroom lawyer, mentioned that many caseworkers really feel they shouldn’t “allow folks” by serving to them: “‘If [clients] are unable to deal with issues, we’re not going to do it for them.’”

The issue is poised to get even worse in Missouri. A number of of the folks I spoke with noticed Smith as being in favor of accelerating the variety of removals. That’s turn out to be significantly clear within the wake of the dying of Grayson O’Connor, a 5-year-old who fell from the window of an residence constructing in late 2023, after the Youngsters’s Division had obtained a number of calls about him. The division has “work to do all through the state on most of these instances,” Smith instructed the native ABC affiliate in response. In August, regardless of telling me that almost all housing-related reviews are dealt with by way of non permanent different placements, Smith despatched a memo to all Youngsters’s Division workers saying that they’re obligated to contemplate whether or not the “imminent hazard” is low sufficient for a brief different placement or the state of affairs is simply too complicated to make use of 1. In that case, the memo instructs, workers should instantly make a request to take away the kid. Instantly afterward, filings for abuse and neglect shot up from a mean of 33 a month between January and July to 95 in August.

“It’s dangerous,” mentioned Snell, the household courtroom lawyer, and “it’s not getting higher.”

Extra from The Nation

As Trump escalates his warfare on civil society, will liberal foundations be part of the combat to defend democracy?

The story ofhis landmark case reminds us of how highly effective a well-liked entrance of socialists and liberals may be in defending our civil liberties.

Take it from me: A crossword clue may be debated with the form of fervor usually reserved for corporatist propaganda and outright racism.

Mainstream media is ignoring the truth that the late intercourse trafficker was an influence dealer who formed world coverage.

Anti-Blackness and race hate more and more appear to be a ceremony of passage for white people, irrespective of the place they find yourself on the political spectrum.