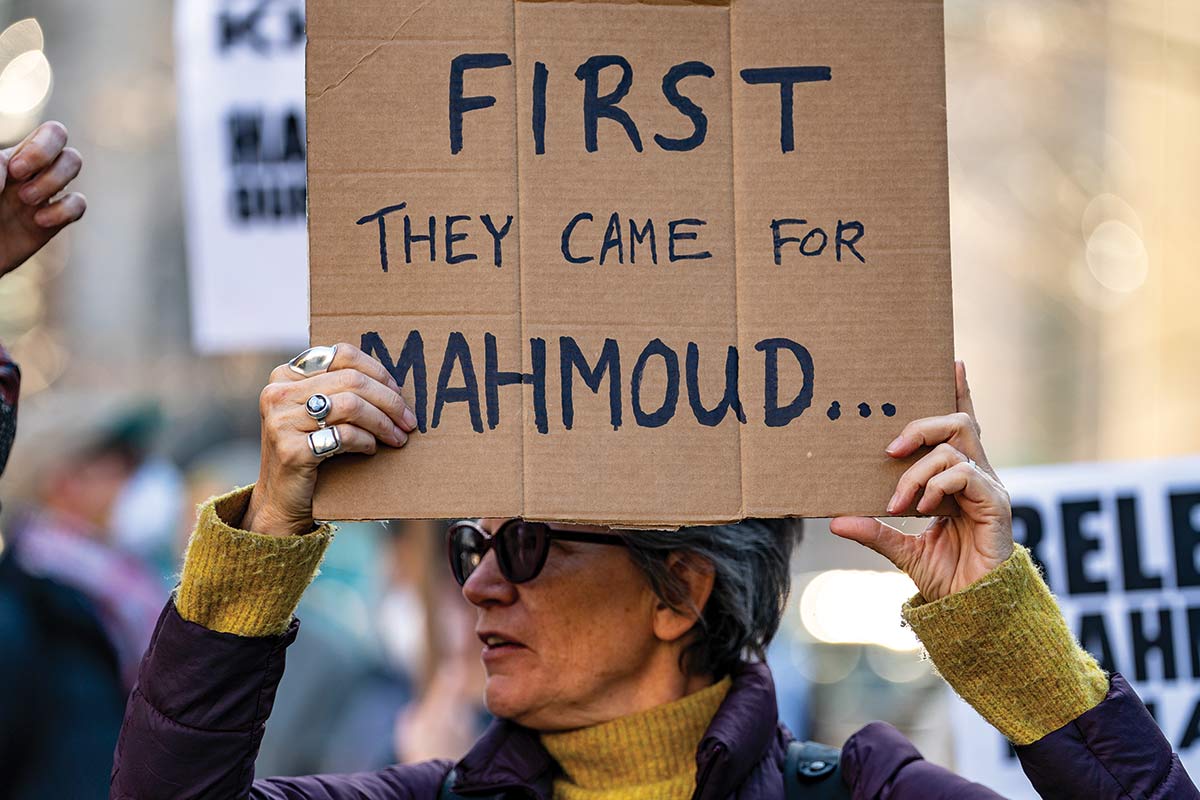

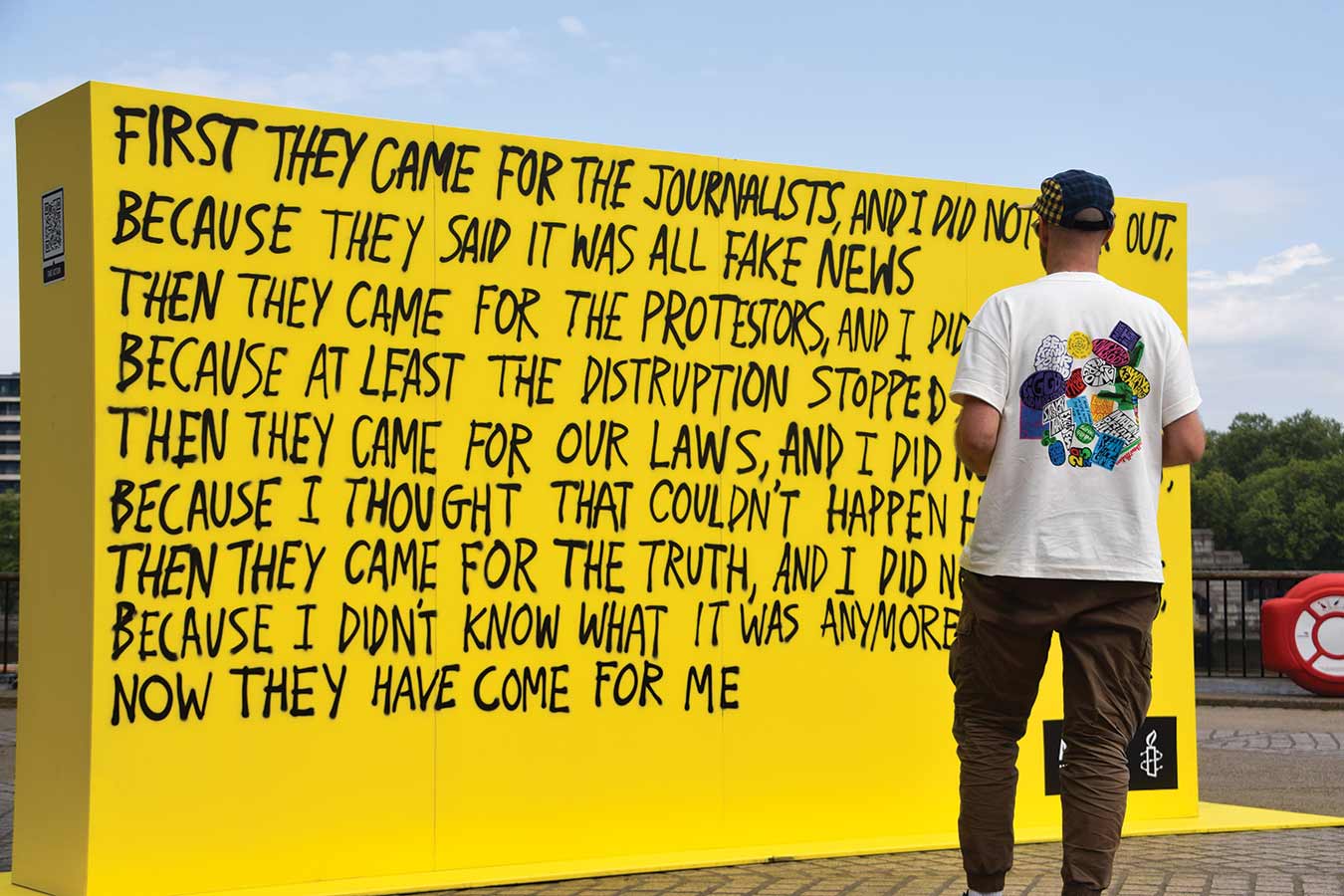

Within the dire months since Donald Trump’s return to energy, you’ve little question learn a model of the well-known mea culpa “First They Got here”—maybe woven into the traces of an essay or op-ed, maybe thumbed out on social media. Half warning, half exhortation, the quick textual content (it’s usually mistaken for a poem) involves us as tragically earned knowledge from the rise of the Nazis, alas grimly related to the America of as we speak. The variation thought-about essentially the most authoritative (if not essentially the most generally cited) reads:

First they got here for the Communists, and I didn’t converse

out—as a result of I used to be not a socialist.

Then they got here for the commerce unionists, and I didn’t converse

out—as a result of I used to be not a commerce unionist.

Then they got here for the Jews, and I didn’t converse out—

as a result of I used to be not a Jew.

Within the many years since these phrases had been formulated, they’ve regularly eclipsed the person chargeable for them, blocking his presence so totally that they arrive on a web page, in some situations, with out a lot as an attribution. However even on these events when Martin Niemöller does get his due, he tends to be credited solely vaguely, as a German pastor who ran afoul of Hitler—his story shorn of its most arduous complexities.

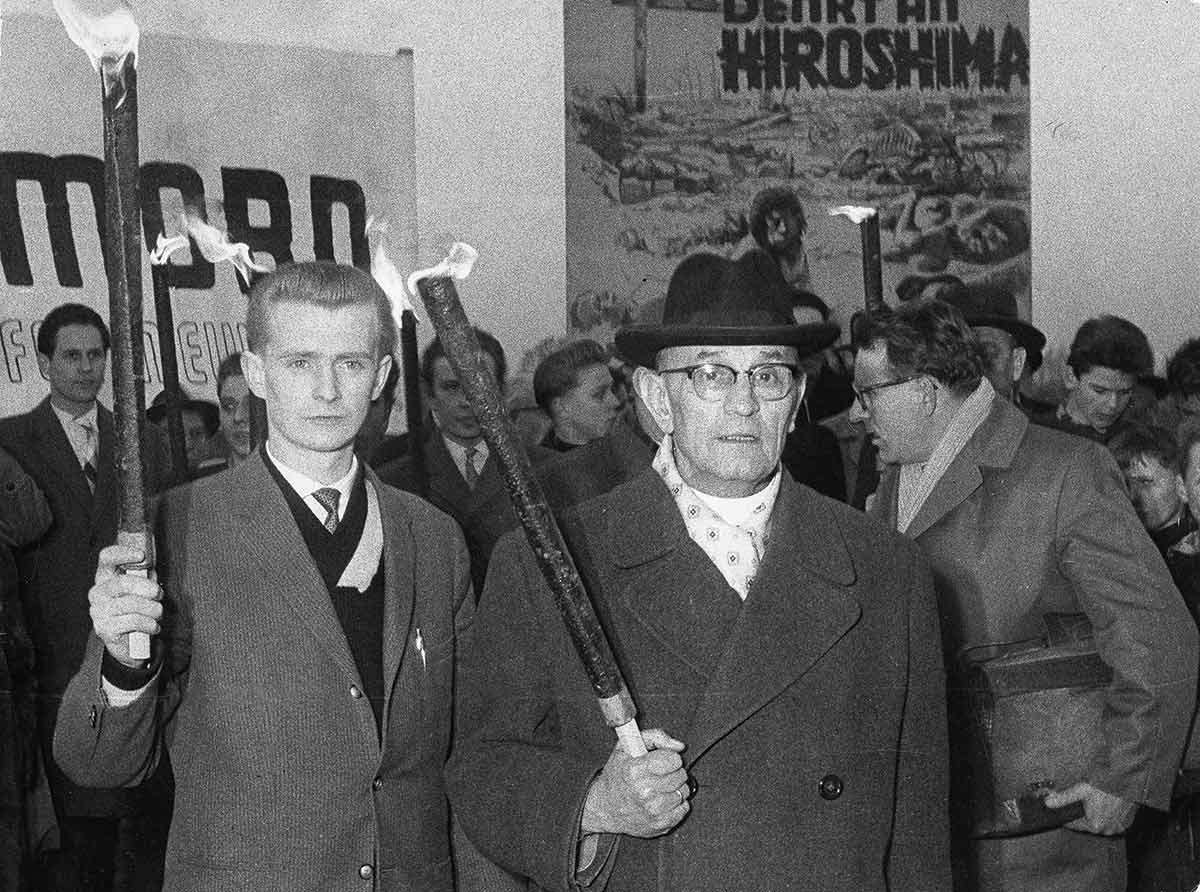

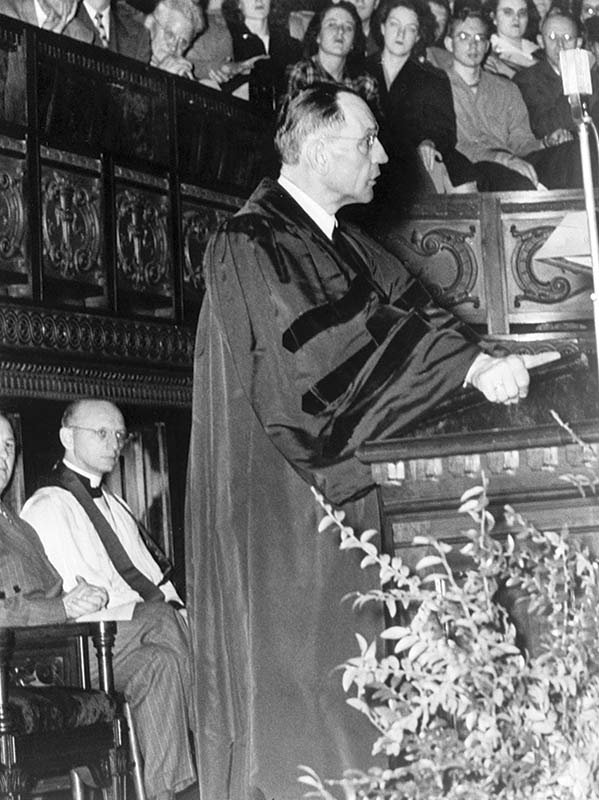

Niemöller was certainly a German cleric, a person world-famous in his day as a defiant martyr for freedom of faith, imprisoned by the Führer for eight lengthy years, till the very finish of World Battle II. Within the years after his launch, Niemöller started providing piecemeal the traces of what would turn into his famed textual content, asserting them in remarks throughout sermons and speeches within the bombed-out ruins of the Third Reich. Whereas the referents typically diversified—some variations included folks with disabilities or Jehovah’s Witnesses, whereas others omitted Communists—the theme remained fixed.

And but, if the textual content tolls the bitter price of indifference and wish of solidarity, it additionally doesn’t go far sufficient with regard to its writer. For all its confessional eloquence, it’s, in actual fact, an act of profound obfuscation: an try and confess guilt with out actually coming clear, to assert duty whereas obscuring what was a deep complicity.

Martin Niemöller had supported Hitler. Enthusiastically. Though he was hailed on the quilt of Time because the “Martyr of 1940” and portrayed in a Hollywood movie as having thundered on the Führer, “Once you assault the Jews, you assault us all!,” the person himself was removed from an anti-fascist freedom fighter. A proud World Battle I hero, he was additionally an imperialist, an ultranationalist, and an antisemite who solely actually objected to the aggressions of the Third Reich after the Nazis started intruding into the area of the Protestant Church. Even then, his objections remained slender. And whereas he did ultimately bear a rare transformation into an indefatigable pacifist and devotee of Gandhi, that transformation got here years after the warfare—a redemption wrenched from the contradictions of a really flawed protagonist.

The historian Benjamin Ziemann, one of many two latest biographers who’ve pierced by the hagiographic shimmer round Niemöller, regards his evolution with one thing near a suspicion of hypocrisy, even duplicity. After marshaling troubling proof of Niemöller’s longtime perspective towards Jews, Ziemann affords in his e-book Hitler’s Private Prisoner that he would revise the enduring mea culpa as follows:

Niemöller’s different revisionist biographer, the historian Matthew Hockenos, takes a extra forgiving strategy. In Then They Got here for Me, he calls Niemöller’s early views and actions repellent however commends his braveness in later life to alter his deeply held beliefs and act accordingly. “On this, Niemöller is to be admired,” Hockenos declares, “and his evolution celebrated.”

So what are we to make of him? And of the textual content whose phrases we quote in these determined instances?

For us, Niemöller’s story presents an abiding problem. Seen in a single mild, his mea culpa is a compromised however nonetheless worthy textual content, its private lesson pressing regardless of its deceptive omissions. Seen in one other, it’s an act of craven concealment hiding behind a present of rueful confession. However there’s a third risk as effectively: that the textual content that got here to be referred to as “First They Got here” is one thing troublesome in an all too human method—a significant knowledge set inside an ethical failure. Its full that means, its uneasy energy, requires us to carry it in each lights collectively.

Lengthy earlier than Martin Niemöller turned a famend worldwide determine—earlier than life’s twists and turns would torque him from a fascist sympathizer into an ecumenical citizen of the world—he was, above all, a patriotic German and a nationalistic Lutheran.

Born in 1892 in Westphalia, in Prussia, he was the second-oldest son of a Lutheran pastor in an imperial Germany underneath the authoritarian Kaiser Wilhelm II. It was a grand Germany again then, a nation of Christian church and state, throne and altar. Obsessive about the Imperial Navy from an early age, by 1918 Niemöller was joyously commanding a U-boat—an particularly harmful posting—having gained an Iron Cross First Class for the motion he’d already seen. When the warfare ended with Germany’s defeat and the kaiser’s abdication, adopted by the turmoil of the 1918–19 revolution that gave option to the Weimar Republic, the profoundly conservative Niemöller was appalled and resigned his fee.

After a quick strive at farming, he determined to turn into a pastor like his father, a safe career in Germany with state funding. However even throughout his theological research in Münster, he didn’t absolutely retreat into the material, as he yearned for the return of Germany’s misplaced imperial glory, abhorred godless Bolshevism, and despised the newly born German republic, its democratic, secularized methods, and its warfare reparations. He led a unit of the Freikorps, the right-wing militia, to place down a staff’ rebellion within the Ruhr area and joined numerous reactionary nationalist teams—together with, Ziemann studies, the primary fascist mass social gathering in Germany, for which he needed to affirm his purely Aryan racial descent.

In 1931, Niemöller arrived because the third pastor at St. Anne’s Church, a prestigious congregation within the rich Dahlem parish in suburban Berlin. He was 39, dynamic, and handsome in a sharp-featured Prussian method, married and with a big household. Each of his fellow St. Anne’s pastors, Ziemann notes, had obtained the Iron Cross First Class as effectively. The congregation included many Nazis and their supporters.

Regardless of his excessive views, Niemöller by no means joined the Nazi Occasion (although his youthful brother, Wilhelm, a pastor too and his future first biographer, was a member from 1923 to 1945, Ziemann studies). However he eagerly supported Hitler’s insurance policies for nationwide renewal and a promised re-Christianization of the nation. A month after Hitler was appointed chancellor in 1933, Niemöller forged his poll for the Nationwide Socialists. From the pulpit that voting day, he primarily celebrated Germany’s reawakening.

Niemöller may need continued alongside this path, “Sieg heil!”–ing his method by the rise of the Third Reich, however solely a month later, the occasions started that will land him in a focus camp.

Underneath the management of Bishop Joachim Hossenfelder, a rising motion of German Christians, which he dubbed “Storm troopers for Christ,” threatened to Nazify the Protestant Church (two-thirds of Germans had been Protestant), melding the swastika with the cross, urging that the Previous Testomony be dropped from the Bible, and denying Jesus’s Jewishness. To this program was added a name for the “Aryan paragraph”—a brand new article in German regulation that disqualified Jews from the civil service—to be utilized to pastors and congregants who had been transformed Jews, thereby overruling the sacramental transformation of baptism.

For Niemöller, and for others, submitting to the Aryan paragraph particularly could be heresy, a violation of Martin Luther’s basic doctrine of two distinct and autonomous kingdoms: the state for earthly governance, the church for religious—each demanding fealty and obedience. It constituted an unacceptable interference within the church’s realm, however German Protestantism’s historical past of being “anti-Judaic” (that’s, theologically antisemitic). Jews had been held chargeable for killing Jesus and thus condemned to their sad destiny. (Niemöller repeated this from the pulpit.) Nazis, for his or her half, favored to cite from Luther’s virulently antisemitic late-in-life tract On the Jews and Their Lies. Niemöller, nevertheless, defended the impartial authority of his realm, the place Jews might be reworked into Christians.

Because the Kirchenkampf (church wrestle) intensified, Niemöller held firmly to this twin—however to his thoughts, absolutely consonant—strategy. Whereas declaring his earthly belief in Hitler, he emerged as a rousing determine of the ecclesiastic opposition, allying with very disparate others such because the younger Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the aesthetic son of a preeminent German psychiatrist, and the honored Swiss leftist theologian Karl Barth. Each Bonhoeffer and Barth known as for talking out in opposition to the Nazis extra forcefully; Bonhoeffer insisted that not solely was the church obliged to succor all victims of Nazi persecution, transformed or not, however, if vital, to jam the spokes of the crushing wheel. He was clear-eyed about his someday ally: “Fantasists and naïves similar to Niemöller,” he wrote to a good friend, “nonetheless suppose they’re true Nationwide Socialists.”

He wasn’t mistaken. In September 1933, Niemöller replied as follows to a parishioner’s request that he publicly condemn the Nazi persecution of all Jews, not simply converts: “The Church doesn’t preach to the state, interfering in its powers (exercised justly or unjustly), which additionally applies to the Jewish query.” He continued, “I additionally affirm the relative proper of our folks to firmly fend off the exaggerated and damaging affect of Jewry that has existed for my part.”

In January 1934, an exasperated Hitler known as the disputing church faction leaders to the Reich Chancellery. It was Niemöller’s sole encounter with the Führer. He wore his Iron Cross. His conduct on the assembly subsequently turned the stuff of widespread delusion, touted lengthy afterward by Niemöller himself. Supposedly, he declared that neither Hitler nor another earthly energy may usurp the church’s God-given authority and duty for its separate area. Ziemann and Hockenos each write that there isn’t any proof for this heroic defiance. Ziemann calls Niemöller’s account a “whitewash” of an encounter that in actual fact was disastrous from the beginning: Hermann Göring, who was current, produced the transcript of a telephone faucet that seemingly implicated Niemöller in conniving to make use of Germany’s president, Paul von Hindenburg, in opposition to Hitler on church points. The surprised pastor struggled to protest, however from then on was snubbed.

“This time the U-boat commander has torpedoed himself,” an ally complained.

After this efficiency and within the wake of the wiretap, the Gestapo arrested Niemöller on quite a few events and held him for questioning. He was required to periodically report back to the authorities. The newly shaped Nazified Reich Church repeatedly suspended him for defying its edicts.

For the following a number of years, Niemöller danced a harmful two-step, shifting boldly between his double loyalties.

In Might 1934, he and the embattled opposition lastly cut up away because the Confessing Church, proclaiming it the true Protestant Church of Germany. Its manifesto, because it had been, was the Barmen Confession, written by Barth. The Nazi state was emphatically instructed that it had no jurisdiction within the realm of Jesus Christ. But that very summer time, Niemöller was as soon as once more reaffirming his nationalist bona fides, writing and rapidly publishing From U-Boat to Pulpit, a memoir of his submarine exploits and his struggles in opposition to the Weimar Republic. By the tip of 1934, it had offered 60,000 copies. Hockenos observes that the writer despatched it to Joseph Goebbels with a be aware saying it was written within the “spirit of the Third Reich.” On the Dahlem church, remarks Ziemann, the pastor would obtain the “Sieg heil!” salute from parishioners, and acknowledge it.

Nonetheless, Niemöller was now talking out ever extra forcefully on the church situation, drawing overflow crowds to his sermons—and gaining worldwide press consideration. Come 1936, having effectively realized that Nationwide Socialism was not re-Christianizing the nation, he was overtly mocking figures like Goebbels. The Gestapo was ever-present: Fellow Confessing Church pastors had been routinely arrested, some despatched to focus camps.

Round this time, Niemöller additionally added his identify to a courageous—albeit strictly confidential—plea to Hitler (principally drafted by others within the Confessing Church) that known as out the Gestapo and the focus camps and even antisemitism extra broadly. It was ignored. On July 1, 1937, the Gestapo arrived but once more on the swish brick Dahlem parsonage and detained him. This time, Niemöller could be held till 1945.

Whereas his arrest provoked worldwide outrage, his well-wishers and the press would have been disturbed in the event that they’d witnessed his protection at a closed path seven months later. There, Ziemann studies, after noting his warfare service and Freikorps doings, Niemöller claimed (falsely, says Ziemann) to have voted for the Nazis even again within the Nineteen Twenties, in addition to acknowledged that Jews had been “alien” to him and that he “disliked” them. He additionally cited his congratulations to Hitler in 1933 for withdrawing from the League of Nations.

Niemöller was cleared of all expenses besides one, whose time he’d already served. However Hitler had no intention of letting such a formidable antagonist get free. At his order, his “private prisoner” was instantly despatched to Sachsenhausen, the principle focus camp for the Berlin area. He’d stay there till 1941, when he was transferred to Dachau, close to Munich, till the tip of the warfare.

Apattern now entrenched itself: the worldwide veneration of Niemöller as a defiant hero, to be jolted by the publicity of ugly contradictions.

It wants emphasizing how lionized an emblem of Nazi resistance Niemöller had turn into. Simply in america, for instance, church buildings everywhere in the nation set their congregations praying for the “combating pastor.” One Brooklyn clergyman restaged Niemöller’s arrest on his pulpit, then delivered his sermon from behind mock Sachsenhausen cell bars. The New York Occasions and Time journal issued common updates on his destiny. Time, as famous, put him on its cowl because the “Martyr of 1940.”

That very same 12 months, the primary film impressed by Niemöller’s heroism, Pastor Corridor, was launched in England, tailored from a 1939 play by the German Jewish exile Ernst Toller. (Sarcastically, Toller had led the very short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic through the German Revolution, which the Freikorps helped crush). Pastor Corridor was delivered to America by James Roosevelt, who bought his mom, Eleanor, to learn a foreword for the US launch. The movie reveals Pastor Corridor being brutally flogged in wretched concentration-camp situations. This was pure invention: Niemöller was by no means bodily abused or punished with compelled labor in all his eight years of imprisonment. The Nazis didn’t wish to improve his martyr standing.

The hosannas that 12 months occurred regardless of the stunning information that had adopted the invasion of Poland in 1939: From Sachsenhausen, Niemöller had petitioned the Nazi navy to serve once more. His request was declined.

Nonetheless, his delusion swelled. In 1944, Paramount Footage made The Hitler Gang, a taut, noirish portrayal of the Nazis’ rise, utilizing actual names, instructed as if Hitler and his henchmen had been gangsters. The movie was directed by John Farrow (Mia’s father) and written principally by the Oscar-nominated group behind The Skinny Man. It featured the one-on-one confrontation scene talked about earlier, with Niemöller now upbraiding the foaming Hitler in regards to the Jews, after having excoriated him: “Do you suppose we’re actually so contemptible that we might give up the sacred religion given to us by God and settle for a political program as a replacement?” Extra invention.

Between these two movies, a e-book appeared: I Was in Hell With Niemöller, by “Leo Stein,” who claimed to have shared a Sachsenhausen cell with the pastor and recorded his humane bravery and his regrets about Hitler. It’s nonetheless cited as we speak; it was a faux, from cowl to cowl.

Niemöller was truly in solitary at Sachsenhausen, although he was allowed occasional temporary, closely monitored visits by his spouse. In Dachau, he additionally obtained visits. He was housed there with three German Catholic clergymen in a separate facility for “particular and honorable” prisoners, together with international inmates with whom he may mingle and share meals. On Christmas Eve 1944, he carried out a profoundly poignant service in a makeshift cell chapel for six fellow Protestants whose nations Germany was besieging or occupying. Within the warfare’s chaotic remaining days—shortly after Bonhoeffer was stripped bare and gruesomely hanged at Flossenbürg camp for his connection to the plot to kill Hitler—Niemöller was rushed away with choose others into northern Italy by SS troops, in keeping with Ziemann to be both murdered or held as a bargaining chip. Hockenos argues for the latter. Niemöller was eventually liberated on Might 4, 1945, to worldwide jubilation.

Did the years of internment change him? Within the instant aftermath of his liberation, it was not solely clear that they’d.

At a press convention organized by US occupation forces, the celebrated image of Nazi resistance defended his newly revealed try and volunteer for navy service from Sachsenhausen: “If there’s a warfare, a German doesn’t ask, is it simply or unjust, however he feels certain to affix the ranks.” He declared—not as a critique—that the German folks weren’t fitted to democracy, longed moderately for authority. He didn’t say he opposed Hitler’s political packages, averring that as a cleric he hadn’t been “” in politics. The New York Occasions grimly assessed that, although admirable in sure methods, the combating pastor was a “singularly ineffectual determine in a rustic and a world crying out for justice.” An appalled Eleanor Roosevelt, Hockenos notes, wrote in her newspaper column that Niemöller’s remarks had been “virtually like a speech from Mr. Hitler.”

However then, one other flip: Hitler’s “private prisoner” was “surprised,” he instructed an Allied interrogator, after studying from American newspapers what had “actually occurred” with the slaughter of Jews. That October, at an Evangelical Church convention in devastated Stuttgart (in Germany, evangelical simply means Protestant), Niemöller helped formulate the Stuttgart Declaration of Guilt. German Protestants, he sermonized, had been guiltier than the Nazis for not having spoken out. “We’re accountable,” the Stuttgart Declaration confessed, “for hundreds of thousands and hundreds of thousands of individuals being murdered, slaughtered, destroyed, thrown into hardship and chased out to international lands, poor human beings, brothers and sisters in all nations of Europe.” Even so, Ziemann notes, there was no particular point out right here of Jews.

A number of weeks later got here the second that Hockenos credit for instigating the extraordinary evolution that Niemöller would bear.

It was at Dachau, the place he stopped to point out his spouse his previous cell. There was a plaque commemorating the various 1000’s who perished on the camp (regardless of its not being a devoted extermination facility)—beginning again in 1933. The 2 guests had been shaken to the core. As Niemöller would go on to repeat to audiences, 1933 was 4 years earlier than he was compelled to silence and ignorance by imprisonment. 4 years when he ought to have spoken out.

Niemöller didn’t resume his pastoral duties on the Dahlem parish. As a substitute, he toured the nation, expressing guilt for not talking out. Such expressions of guilt weren’t effectively obtained by his countrymen. Particularly when he pressed the matter additional, calling on Germans now to collectively take duty for the Holocaust, declaring in a Might 1946 sermon, in keeping with Hockenos: “Six million Jews, a whole folks, had been cold-bloodedly murdered in our midst and in our identify…. Now we have to simply accept the burden of that legacy.” It was throughout this time that Niemöller’s well-known credo started to emerge in bits and items.

All of the whereas, extra Niemöller contradictions. He railed in regards to the remedy of the German folks by the occupation forces. He fiercely opposed denazification as far too blunt and punitive an instrument, insisting it might solely additional victimize struggling Germans. “There’s a new antisemitism in Germany,” he contended in an announcement quoted by Ziemann. “It’s brought on by the Individuals letting Jews perform the denazification.” There have been different such ugly outbursts.

Even so, America was clamoring—over the objections of some outstanding figures—for him to go to. In late 1946, regardless of vehement disapproval from Eleanor Roosevelt, main rabbi Stephen Clever, and others, Niemöller and his spouse arrived for an American tour—the primary outstanding German civilians to be granted US visas after the warfare. For 5 months, Niemöller barnstormed the nation, addressing overflow audiences in English. In New York, he met Reinhold Niebuhr; in Hollywood, John Farrow, the director of The Hitler Gang, and Bing Crosby, whose priestly flip in Going My Method he admired. He was usually on the radio. He recited “First They Got here” solely as soon as, at his lone look earlier than a German-speaking viewers. His overriding concern was to foyer for American support to his shattered, ravenous homeland. His tour was an incredible success personally, in addition to financially for Germany.

Again within the distress of his homeland—the place he discovered himself denied sufferer standing by the German Affiliation of the Victims of the Nazi Regime, largely for his statements following his 1937 arrest—Niemöller turned the primary president of the newly shaped Evangelical Church of Hesse and Nassau, which included Frankfurt. There, he fought ferociously in opposition to denazification. On the identical time, because the chairman of the Evangelical Church’s international workplace, he started to journey extensively, then extra extensively, making an attempt to reestablish to the world the non secular legitimacy of the German Protestant Church after the horrors of Nazism.

For this author, Niemöller’s globe-spanning travels had been a significant factor in his evolution. From right here on, the compass of the final 4 many years of his lengthy life would swing by levels in an more and more radical—one would possibly even say miraculous—route. Maybe the dedicated nationalist was lastly modified by his contact with the extensive, multi-faith, multifaceted world (an publicity that constructed on his ecumenical fellowship behind the barbed wire of Dachau, which Hockenos sees as a deeply affecting expertise). Or maybe, as soon as the gears of self-reflection and remorse started to show, particularly after his go to to Dachau, he did what few folks do: He allow them to flip and maintain turning, pushing him ever tougher within the route of justice.

Bitterly against the 1949 partition of Germany, Niemöller visited church buildings within the Communist GDR, after which even Orthodox ones in Russia, for which he drew harsh criticism not simply in West Germany however within the US, and which led to his ousting from the church international workplace in 1965. Nonetheless, he continued. He traveled all through Asia and Africa, coming to treat the International South as true Christianity’s future. He turned a copresident of the World Council of Church buildings from 1961 to 1968, resigning halfway as president of the Hesse and Nassau church and ultimately turning away from institutional Christianity. He tried, he stated, to behave in imitation of Christ on this planet—declaring in 1975, “Like my Lord and Savior Jesus I stand by those that have been deserted by everybody—together with the communists—the outcasts, the wretched, the famishing, and the ravenous.” (He even stated at one level that pastors might be Communists.)

He turned celebrated as a world “ambassador of God,” one who overtly intruded now into the realm of the state, an Iron Cross hero turned high-profile pacifist (after a harrowing 1954 dialog in regards to the hydrogen bomb with the Nobel Prize–profitable nuclear chemist Otto Hahn) and Gandhi admirer—a vocal exponent of social justice, anti-nationalism, anti-colonialism, and anti-racism and an opponent of apartheid. He shared a stage with Martin Luther King Jr., met with and praised Ho Chi Minh through the Vietnam Battle. He turned a outstanding fixture of the worldwide anti-nuclear motion and accepted the Lenin Peace Prize. A relentless critic of West Germany and its rearmament, he backed the nation’s youthful upheaval of 1968.

“Aged 90, I’m now a revolutionary,” he instructed Stern journal in 1982, two years earlier than his dying. “If I reside to be 100, perhaps I’ll be an anarchist.”

Whereas Hockenos salutes the extraordinary transformation of this German ultra-conservative, together with his “repellent” early views, into somebody with the braveness to alter deeply held beliefs, Ziemann will not be so forgiving. He traces unsettling continuities, with notably acute sensitivity to Niemöller’s conduct relating to Jews. In all his globe-trotting, as an illustration, the ambassador of God by some means by no means set foot in Israel. Ziemann indicts Niemöller for remarks similar to saying in 1963 that he couldn’t maintain it in opposition to Arabs in the event that they felt “threatened and underneath assault” by the Jewish state. Or, in 1967, privately expressing that if he had been an Arab, he’d be “antisemitic” about an “alien folks founding a state on his soil.”

One would possibly agree with the gist of Niemöller’s remarks (although Ziemann doesn’t), however given his historical past, there stays a lingering odor of antisemitism.

How, then, can we weigh the case of Martin Niemöller? Actually he stays… “sophisticated.” Contradictions unresolved. For all of the bravery he confirmed and the nice he promoted, for all of the methods he developed, he stays flawed. A problem.

And but this problem is instructive.

When the present age of cruelty lastly involves an finish, a few of its enablers will little question proclaim their regrets. Maybe they’ll lament that they didn’t perceive the complete import of Trump’s actions. Or that they failed to withstand as a result of they didn’t see themselves mirrored in MAGA’s victims. Or had been afraid they’d be subsequent. However no matter their explanations, we might do effectively to recollect Niemöller’s instance and attend not solely to their phrases however to what’s left unsaid and unacknowledged. To what, we must always ask, are they really confessing? For what are they apologizing? And, most vital of all, what’s going to they then do about it?

Nor ought to we cease there. Martin Niemöller’s story additionally calls for one thing of us—we who nod righteously as we learn his mea culpa, happy within the information that we aren’t silent, that we perceive. As we now know, Niemöller’s story is a warning not merely about indifference however in regards to the sneaky, self-deluding energy of complicity. It’s a reminder to query the actual energy of our empathy, and to withstand the lure of complacency. Most of all, maybe, it’s a prod, a spur to do the specific factor the German pastor mentions solely figuratively when he laments his failure to “converse out.” We should act.

Extra from The Nation

The brand new present from the creators of The Workplace reminds us that their comedic type does now work in each “office on this planet.”

An excellent prose stylist, assured, amiable, and splendidly lucid when speaking about different folks’s issues, Updike not often confessed or confronted his personal.

The corporate has reworked the very nature of social media, and within the course of it has mutated as effectively—from tech unicorn to geopolitical chesspiece.